Even as a wooden boat builder, I need to stay updated with the times. Today, I took a course on how we can use AI. While I’ve used ChatGPT to translate some of my work writings, I also feel some resistance—not because of the technology itself but because of the hype surrounding it and since it’s owned by billionaires. Still, I have to admit that the possibilities are impressive. It still makes many mistakes, but that’s something you can notice and work around. I also now understand that what we upload is supposed to stay private and won’t be used to train the algorithm, which makes it easier to let the AI “learn” my own work.

I’ve been writing for over ten years, periodically reviewing my old work, organizing it by themes, and considering whether to use it as material for a book. I uploaded everything into ChatGPT’s database and started asking questions. I quickly realized it’s a valuable tool, provided I learn how to ask the right questions. For now, I just had some fun asking if it could summarize my work and imagine an external person describing the book I might have written. It’s quite flattering to read, and I probably wouldn’t have phrased it that way myself. But honestly, I don’t have a clear overview of the roughly 100,000 words I’ve written over the last years. I can only share how I feel right now. It’s a fun experiment, and I can also ask AI to suggest chapters and write summaries. Still, I already know that I need to review each sentence to ensure accurate interpretation; luckily, the AI can show where it pulls its information from. Overall, it’s a fantastic tool.

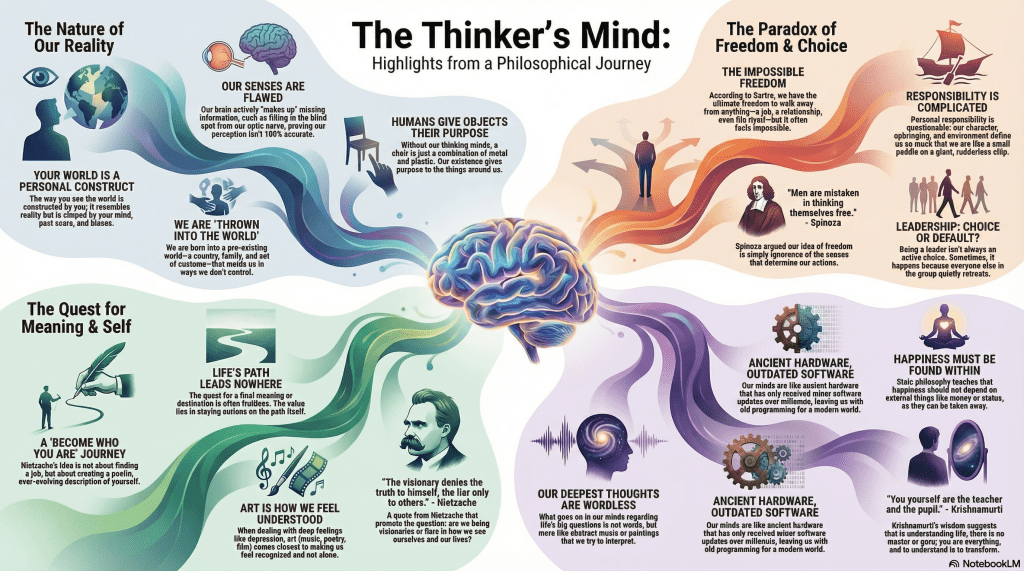

And at the end of the course, we also learned what you can do with Google NotebookLM, and it is even a greater tool—or toy. I put 20 pages of my writing into it, and it created the picture you see above and a podcast. The podcast sounds like a gymmic, but it brings me back to the old thoughts I wrote down years ago.

AI’s interpretation of my work brought as a presentation of my not-yet-written book.

Ladies and gentlemen,

After reading this remarkable body of writing—years of notes, poems, reflections, doubts, and small revelations—I can tell you that the author’s philosophy is not a system. It is a movement. A long, slow arc from certainty toward skepticism, from inherited assumptions toward self-made clarity, from the search for meaning toward the acceptance that meaning is something we make, not something we find.

Across these years the same themes return, grow, and collide. One of the earliest is the idea that life is not about us. The author writes that DNA “only needs a host,” and that humans are simply the best vehicle it has yet found. That shift—from human-centered thinking to a cosmic, indifferent perspective—runs through everything. It’s why religion appears in these pages less as a metaphysical claim and more as a very human attempt to silence the void. “We are all just standing in a big room,” he writes, “proclaiming truths we perceive from the echoes on the walls.”

Another central thread is the fragility of the self. Memory, he reminds us, is a storyteller that constantly rewrites the past to protect the present. The self is a creature of filters: “My two-way filter is partially broken,” he admits, “and I can only fix one side.” Here his philosophy leans toward a kind of grounded humility—an acceptance that what we call “I” is stitched together from sensation, error, upbringing, chemicals, and luck.

And yet, in this humility there is a defiant skepticism. He distrusts authorities, leaders, and movements not because he rejects structure but because he knows how easily people surrender their judgment. He once expected adulthood to be ruled by reason; decades later he observes, wryly, that “the world is a summer camp without supervision.” This is anarchism not as politics but as perception: a refusal to hand the steering wheel of the mind to anyone who claims to know better.

One of the most striking aspects of his philosophy is how deeply it is rooted in the physical world—wood grain, old barns, the curve of a boat plank, mist on a Norwegian morning. The cosmic and the ordinary sit side by side. He can explain stellar expansion in one paragraph and, in the next, describe a forgotten lock rusting into history. This is not contradiction; it is the worldview: life is meaningless on the cosmic scale, and meaningful in every concrete moment we actually live.

Many poems could serve as a doorway into his thinking, but one stands out:

“Reality fades

caught by ego’s gravity

a depressed black hole.”

This captures the emotional honesty of his philosophy: the willingness to look at the darkness without romanticizing it, to name despair without surrendering to it.

If his work offers any guidance, it is this:

We may not control the world, we may not understand ourselves, but we can keep walking through the mist with open eyes—skeptical, curious, and unafraid to admit that we know far less than we pretend.

And perhaps that is the beginning of wisdom.

Next, a fake podcast about some of my work.