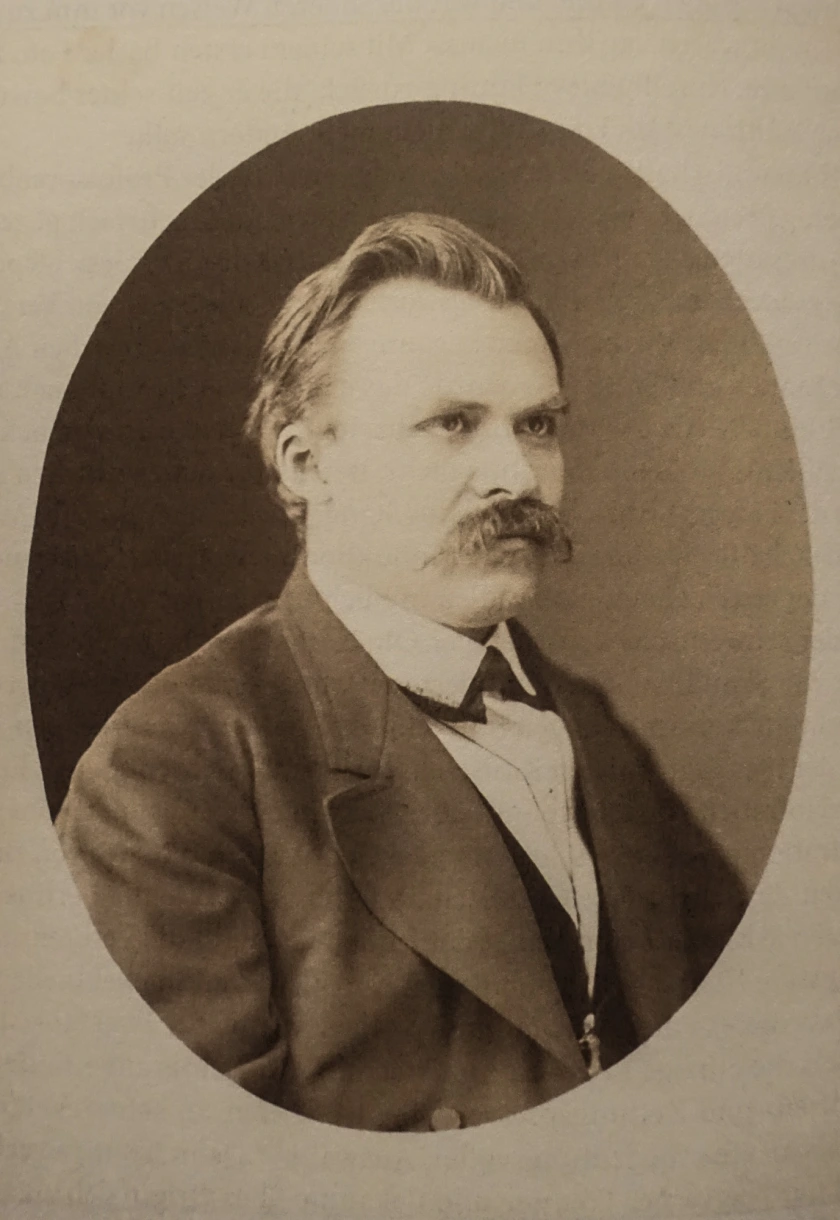

Reading Friedrich Nietzsche’s Human all too human

Read the introduction here You can read the aphorism I discuss here in English and German below the main article.

My take on it/synopsis.

-

Mistaken origin of free will and feelings.

The history of the impression we use to judge someone’s responsibility for their actions has the following stages. First you have good and bad actions that are judged by the results, soon these results are forgotten, and the actions are now just good or bad. Then the goodness or badness is implanted in the motive, and the action in itself is looked upon as morally ambiguous. Than we goes further by designating good or bad to a whole person instead of their actions. To evaluate, man is made responsible for his effects (the results), then for his actions, then for his motives, and finally for his nature. But finally, man discovers that our nature is determined by his place in time and space and that there is no free will. Schopenhauer does not agree with this and points out that some actions give you guild and therefore require the need for you to be responsible, if you were not responsible you could not have felt guild. But man himself, because of his determinism, is precisely the being that he is—which Schopenhauer denies. Because we can feel guild Schopenhauer thinks he can prove our liberty not with regard to what we do, but with regard to our nature, we have the freedom to be this or that way, but we cannot act this or that way. Out of the sphere of freedom and responsibility, comes the sphere of strict causality, necessity, and irresponsibility. The feeling of guild comes apparently from causality, but in reality, it comes from our freedom which is the action of a free will, the fundamental cause of the existence of an individual, his will is there before his existence. Here the twisted reasoning is followed, that the fact that there is guilt inferred the justification, the rational acceptability comes from this, this is how Schopenhauer arrives at his fantastic sequence of the so-called intelligible freedom. But the guild after the deed is not necessarily reasonable, it is most certainly not, because it is based on the wrong presumption that the feeling of guild is not a necessary result. Therefore, it is only because man believes himself to be free, not because he is free, that he experiences guild. Guild is also something you can unlearn, and it also depends on where you live, in what kind of culture, we don’t even know how old this feeling is. Nobody is responsible for his actions, nobody for his nature, to judge is identical with being unjust. This also applies when an individual judges himself. The theory is as clear as sunlight, and yet everyone prefers to go back into the shadow and the untruth, for fear of the consequences.

The history of the impression we use to judge someone’s responsibility for their actions has the following stages. First you have good and bad actions that are judged by the results, soon these results are forgotten, and the actions are now just good or bad. Then the goodness or badness is implanted in the motive, and the action in itself is looked upon as morally ambiguous. Than we goes further by designating good or bad to a whole person instead of their actions. To evaluate, man is made responsible for his effects (the results), then for his actions, then for his motives, and finally for his nature. But finally, man discovers that our nature is determined by his place in time and space and that there is no free will. Schopenhauer does not agree with this and points out that some actions give you guild and therefore require the need for you to be responsible, if you were not responsible you could not have felt guild. But man himself, because of his determinism, is precisely the being that he is—which Schopenhauer denies. Because we can feel guild Schopenhauer thinks he can prove our liberty not with regard to what we do, but with regard to our nature, we have the freedom to be this or that way, but we cannot act this or that way. Out of the sphere of freedom and responsibility, comes the sphere of strict causality, necessity, and irresponsibility. The feeling of guild comes apparently from causality, but in reality, it comes from our freedom which is the action of a free will, the fundamental cause of the existence of an individual, his will is there before his existence. Here the twisted reasoning is followed, that the fact that there is guilt inferred the justification, the rational acceptability comes from this, this is how Schopenhauer arrives at his fantastic sequence of the so-called intelligible freedom. But the guild after the deed is not necessarily reasonable, it is most certainly not, because it is based on the wrong presumption that the feeling of guild is not a necessary result. Therefore, it is only because man believes himself to be free, not because he is free, that he experiences guild. Guild is also something you can unlearn, and it also depends on where you live, in what kind of culture, we don’t even know how old this feeling is. Nobody is responsible for his actions, nobody for his nature, to judge is identical with being unjust. This also applies when an individual judges himself. The theory is as clear as sunlight, and yet everyone prefers to go back into the shadow and the untruth, for fear of the consequences.

Text from the translation by Helen Zimmern and my take on it

The history of the sentiments by means of which we make a person responsible consists of the following principal phases. The history of the impression we use to judge someone’s responsibility for their actions has the following stages. First, all single actions are called good or bad without any regard to their motives, but only on account of the useful or injurious consequences which result for the community. First you have good and bad action that are judged by the results, But soon the origin of these distinctions is forgotten, and it is deemed that the qualities ” good ” or ” bad ” are contained in the action itself without regard to its consequences, Soon the results are forgotten and the actions are now just good or bad. by the same error according to which language describes the stone as hard,the tree as green,—with which, in short, the result is regarded as the cause. Then the goodness or badness is implanted in the motive, and the action in itself is looked upon as morally ambiguous. Then the goodness or badness is implanted in the motive, and the action in itself is looked upon as morally ambiguous. Mankind even goes further, and applies the predicate good or bad no longer to single motives, but to the whole nature of an individual, out of whom the motive grows as the plant grows out of the earth. Than man goes further by designating good or bad to a whole person instead of their actions. Thus, in turn, man is made responsible for his operations, then for his actions, then for his motives, and finally for his nature. To evaluate, man is made responsible for his effects, then for his actions, then for his motives, and finally for his nature. Eventually it is discovered that even this nature cannot be responsible, inasmuch as it is an absolutely necessary consequence concreted out of the elements and influences of past and present things,—that man, therefore, cannot be made responsible for anything, neither for his nature, nor his motives, nor his actions, nor his effects. It has therewith come to be recognised that the history of moral valuations is at the same time the history of an error, the error of responsibility, which is based upon the error of the freedom of will. But finally man discovers that our nature is determined by his place in time and space and that there is no free will. Schopenhauer thus decided against it: because certain actions bring ill humour (“consciousness of guilt”) in their train, there must be a responsibility ; for there would be no reason for this ill humour if not only all human actions were not done of necessity,—which is actually the case and also the belief of this philosopher, Schopenhauer does not agree and points out that some actions give you guild and therefore needs you to be responsible, if you were not responsible you could not have felt guild, and Schopenhauer agrees with this. —but man himself from the same necessity is precisely the being that he is—which Schopenhauer denies. but man himself from the same necessity is precisely the being that he is—which Schopenhauer denies. From the fact of that ill humour Schopenhauer thinks he can prove a liberty which man must somehow have had, not with regard to actions, but with regard to nature Because we can feel guild Schopenhauer thinks he can prove our liberty not with regard to actions, but with regard to nature ; liberty, therefore, to be thus or otherwise, not to act thus or otherwise. From the esse, the sphere of freedom and responsibility, there results, in his opinion, the operari, the sphere of strict causality, necessity, and irresponsibility. We have the freedom to be this or that way, but we cannot act this or that way. From the sphere of freedom and responsibility, there results, in his opinion, the sphere of strict causality, necessity, and irresponsibility. This ill humour is apparently directed to the operari,—in so far it is erroneous,—The feeling of guild comes aperently from causality, but in reality it is directed to the esse, but in reality it comes from our freedom which is the deed of a free will, the fundamental cause of the existence of an individual, which is the deed of a free will, the fundamental cause of the existence of an individual man becomes that which he wishes to be, his will is anterior to his existence. His will is there before his existence. Here the mistaken conclusion is drawn that from the fact of the ill humour, the justification, the reasonable admissableness of this ill humour is presupposed ; and starting from this mistaken conclusion, Schopenhauer arrives at his fantastic sequence of the so-called intelligible freedom. Here the twisted reasoning is followed, that from guilt the justification, the rational acceptability of this regret is derived, this is how Schopenhauer arrives at his fantastic sequence of the so-called intelligible freedom. But the ill humour after the deed is not necessarily reasonable, indeed it is assuredly not reasonable, But the guild after the deed is not necessarily reasonable, it is most certainly not, for it is based upon the erroneous presumption that the action need not have inevitably followed. Because it is based on the wrong presumption that the feeling of guild is not a necessary result. Therefore, it is only because man believes himself to be free, not because he is free, that he experiences remorse and pricks of conscience. Therefore, it is only because man believes himself to be free, not because he is free, that he experiences guild.Moreover, this ill humour is a habit that can be broken off; in many people it is entirely absent in connection with actions where others experience it. It is a very changeable thing, and one which is connected with the development of customs and culture, and probably only existing during a comparatively short period of the world’s history. Guild is also something you can unlearn, and it also depends on where you live, in what kind of culture. We don’t even know how old this feeling is. Nobody is responsible for his actions, nobody for his nature ; to judge is identical with being unjust. Nobody is responsible for his actions, nobody for his nature ; to judge is identical with being unjust. This also applies when an individual judges himself. The theory is as clear as sunlight, and yet every one prefers to go back into the shadow and the untruth, for fear of the consequences. This also applies when an individual judges himself. The theory is as clear as sunlight, and yet every one prefers to go back into the shadow and the untruth, for fear of the consequences.

Human, all too human a book for free spirits Part I translated by Helen Zimmern 1909

- THE FABLE OF INTELLIGIBLE FREEDOM.—The history of the sentiments by means of which we make a person responsible consists of the following principal phases. First, all single actions are called good or bad without any regard to their motives, but only on account of the useful or injurious consequences which result for the community. But soon the origin of these distinctions is forgotten, and it is deemed that the qualities ” good ” or ” bad ” are contained in the action itself without regard to its consequences, by the same error according to which language describes the stone as hard,the tree as green,—with which, in short, the result is regarded as the cause. Then the goodness or badness is implanted in the motive, and the action in itself is looked upon as morally ambiguous. Mankind even goes further, and applies the predicate good or bad no longer to single motives, but to the whole nature of an individual, out of whom the motive grows as the plant grows out of the earth. Thus, in turn, man is made responsible for his operations, then for his actions, then for his motives, and finally for his nature. Eventually it is discovered that even this nature cannot be responsible, inasmuch as it is an absolutely necessary consequence concreted out of the elements and influences of past and present things,—that man, therefore, cannot be made responsible for anything, neither for his nature, nor his motives, nor his actions, nor his effects. It has therewith come to be recognised that the history of moral valuations is at the same time the history of an error, the error of responsibility, which is based upon the error of the freedom of will. Schopenhauer thus decided against it: because certain actions bring ill humour (“consciousness of guilt”) in their train, there must be a responsibility ; for there would be no reason for this ill humour if not only all human actions were not done of necessity,—which is actually the case and also the belief of this philosopher,—but man himself from the same necessity is precisely the being that he is—which Schopenhauer denies. From the fact of that ill humour Schopenhauer thinks he can prove a liberty which man must somehow have had, not with regard to actions, but with regard to nature ; liberty, therefore, to be thus or otherwise, not to act thus or otherwise. From the esse, the sphere of freedom and responsibility, there results, in his opinion, the operari, the sphere of strict causality, necessity, and irresponsibility. This ill humour is apparently directed to the operari,—in so far it is erroneous,—but in reality it is directed to the esse, which is the deed of a free will, the fundamental cause of the existence of an individual, man becomes that which he wishes to be, his will is anterior to his existence. Here the mistaken conclusion is drawn that from the fact of the ill humour, the justification, the reasonable admissableness of this ill humour is presupposed ; and starting from this mistaken conclusion, Schopenhauer arrives at his fantastic sequence of the so-called intelligible freedom. But the ill humour after the deed is not necessarily reasonable, indeed it is assuredly not reasonable, for it is based upon the erroneous presumption that the action need not have inevitably followed. Therefore, it is only because man believes himself to be free, not because he is free, that he experiences remorse and pricks of conscience. Moreover, this ill humour is a habit that can be broken off; in many people it is entirely absent in connection with actions where others experience it. It is a very changeable thing, and one which is connected with the development of customs and culture, and probably only existing during a comparatively short period of the world’s history. Nobody is responsible for his actions, nobody for his nature ; to judge is identical with being unjust. This also applies when an individual judges himself. The theory is as clear as sunlight, and yet every one prefers to go back into the shadow and the untruth, for fear of the consequences.

Menschliches allzu menschlich 1878/80

- Die Fabel von der intelligibelen Freiheit. – Die Geschichte der Empfindungen, vermöge deren wir jemanden verantwortlich machen, also der sogenannten moralischen Empfindungen verläuft, in folgenden Hauptphasen. Zuerst nennt man einzelne Handlungen gut oder böse ohne alle Rücksicht auf deren Motive, sondern allein der nützlichen oder schädlichen Folgen wegen. Bald aber vergisst man die Herkunft dieser Bezeichnungen und wähnt, dass den Handlungen an sich, ohne Rücksicht auf deren Folgen, die Eigenschaft “gut” oder “böse” innewohne: mit demselben Irrthume, nach welchem die Sprache den Stein selber als hart, den Baum selber als grün bezeichnet – also dadurch, dass man, was Wirkung ist, als Ursache fasst. Sodann legt man das Gut- oder Böse-sein in die Motive hinein und betrachtet die Thaten an sich als moralisch zweideutig. Man geht weiter und giebt das Prädicat gut oder böse nicht mehr dem einzelnen Motive, sondern dem ganzen Wesen eines Menschen, aus dem das Motiv, wie die Pflanze aus dem Erdreich, herauswächst. So macht man der Reihe nach den Menschen für seine Wirkungen, dann für seine Handlungen, dann für seine Motive und endlich für sein Wesen verantwortlich. Nun entdeckt man schliesslich, dass auch dieses Wesen nicht verantwortlich sein kann, insofern es ganz und gar nothwendige Folge ist und aus den Elementen und Einflüssen vergangener und gegenwärtiger Dinge concrescirt: also dass der Mensch für Nichts verantwortlich zu machen ist, weder für sein Wesen, noch seine Motive, noch seine Handlungen, noch seine Wirkungen. Damit ist man zur Erkenntniss gelangt, dass die Geschichte der moralischen Empfindungen die Geschichte eines Irrthums, des Irrthums von der Verantwortlichkeit ist: als welcher auf dem Irrthum von der Freiheit des Willens ruht. -Schopenhauer schloss dagegen so: weil gewisse Handlungen Unmuth (“Schuldbewusstsein”) nach sich ziehen, so muss es eine Verantwortlichkeit geben; denn zu diesem Unmuth wäre kein Grund vorhanden, wenn nicht nur alles Handeln des Menschen mit Nothwendigkeit verliefe – wie es thatsächlich, und auch nach der Einsicht dieses Philosophen, verläuft -, sondern der Mensch selber mit der selben Nothwendigkeit sein ganzes Wesen erlangte, – was Schopenhauer leugnet. Aus der Thatsache jenes Unmuthes glaubt Schopenhauer eine Freiheit beweisen zu können, welche der Mensch irgendwie gehabt haben müsse, zwar nicht in Bezug auf die Handlungen, aber in Bezug auf das Wesen: Freiheit also, so oder so zu sein, nicht so oder so zu handeln. Aus dem esse, der Sphäre der Freiheit und Verantwortlichkeit, folgt nach seiner Meinung das operari, die Sphäre der strengen Causalität, Nothwendigkeit und Unverantwortlichkeit. Jener Unmuth beziehe sich zwar scheinbar auf das operari – insofern sei er irrthümlich -, in Wahrheit aber auf das esse, welches die That eines freien Willens, die Grundursache der Existenz eines Individuums, sei; der Mensch werde Das, was er werden wolle, sein Wollen sei früher, als seine Existenz. – Hier wird der Fehlschluss gemacht, dass aus der Thatsache des Unmuthes die Berechtigung, die vernünftige Zulässigkeit dieses Unmuthes geschlossen wird; und von jenem Fehlschluss aus kommt Schopenhauer zu seiner phantastischen Consequenz der sogenannten intelligibelen Freiheit. Aber der Unmuth nach der That braucht gar nicht vernünftig zu sein: ja er ist es gewiss nicht, denn er ruht auf der irrthümlichen Voraussetzung, dass die That eben nicht nothwendig hätte erfolgen müssen. Also: weil sich der Mensch für frei hält, nicht aber weil er frei ist, empfindet er Reue und Gewissensbisse. – Ueberdiess ist dieser Unmuth Etwas, das man sich abgewöhnen kann, bei vielen Menschen ist er in Bezug auf Handlungen gar nicht vorhanden, bei welchen viele andere Menschen ihn empfinden. Er ist eine sehr wandelbare, an die Entwickelung der Sitte und Cultur geknüpfte Sache und vielleicht nur in einer verhältnissmässig kurzen Zeit der Weltgeschichte vorhanden. -Niemand ist für seine Thaten verantwortlich, Niemand für sein Wesen; richten ist soviel als ungerecht sein. Diess gilt auch, wenn das Individuum über sich selbst richtet. Der Satz ist so hell wie Sonnenlicht, und doch geht hier jedermann lieber in den Schatten und die Unwahrheit zurück: aus Furcht vor den Folgen.

Sources:

I will read a Dutch translation that is based on the work of researchers Colli and Montinari. I also use a translation from R.J.Hollingdale and the Gary Handwerk translation from the Colli-Montinari edition. Both are more modern than the copyright free translation I use here. This is a translation from 1909 by Helen Zimmern, who knew Nietzsche personally, but there was no critical study of Nietzsche’s work done back then and this translation suffers from that. The same goes for the translation from Alexander Harvey. My German is not good enough to pretend that I can translate it better than the professionals do but I will use the original as a referee.

- Menselijk al te menselijk een boek voor vrije geesten, translated by Thomas Graftdijk, 2000. Buy it here

- Human, all too human a book for free spirits, translated by R.J.Hollingdale, 1986

- Human, all too human a book for free spirits I V3, translated by Gary handwerk 1997

- Human, all too human a book for free spirits Part I, translated by Helen Zimmern 1909. Read it here

- Human, all too human a book for free spirits, translated by Alexander Harvey, 1908. Read it here

- Menschliches allzu menschlich 1878/80. Read it here

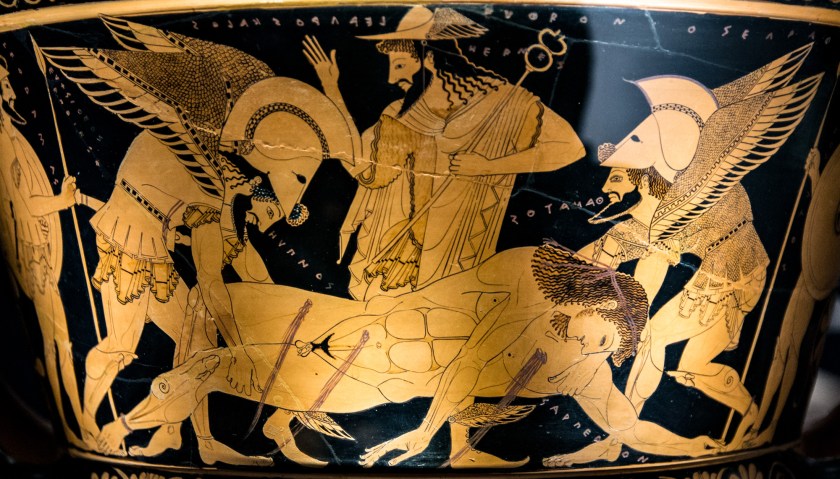

The animal in us likes to be lied to, morality is a lie for our own good because the truth will destroy us. Without this lie we would still be animals, but it made us feel better and we laid stricter laws on ourselves. That’s why we hate the earlier parts of our development because it is closer to our beginnings, and that can explain the hatred for slaves.

The animal in us likes to be lied to, morality is a lie for our own good because the truth will destroy us. Without this lie we would still be animals, but it made us feel better and we laid stricter laws on ourselves. That’s why we hate the earlier parts of our development because it is closer to our beginnings, and that can explain the hatred for slaves.

The history of the impression we use to judge someone’s responsibility for their actions has the following stages. First you have good and bad actions that are judged by the results, soon these results are forgotten, and the actions are now just good or bad. Then the goodness or badness is implanted in the motive, and the action in itself is looked upon as morally ambiguous. Than we goes further by designating good or bad to a whole person instead of their actions. To evaluate, man is made responsible for his effects (the results), then for his actions, then for his motives, and finally for his nature. But finally, man discovers that our nature is determined by his place in time and space and that there is no free will. Schopenhauer does not agree with this and points out that some actions give you guild and therefore require the need for you to be responsible, if you were not responsible you could not have felt guild. But man himself, because of his determinism, is precisely the being that he is—which Schopenhauer denies. Because we can feel guild Schopenhauer thinks he can prove our liberty not with regard to what we do, but with regard to our nature, we have the freedom to be this or that way, but we cannot act this or that way. Out of the sphere of freedom and responsibility, comes the sphere of strict causality, necessity, and irresponsibility. The feeling of guild comes apparently from causality, but in reality, it comes from our freedom which is the action of a free will, the fundamental cause of the existence of an individual, his will is there before his existence. Here the twisted reasoning is followed, that the fact that there is guilt inferred the justification, the rational acceptability comes from this, this is how Schopenhauer arrives at his fantastic sequence of the so-called intelligible freedom. But the guild after the deed is not necessarily reasonable, it is most certainly not, because it is based on the wrong presumption that the feeling of guild is not a necessary result. Therefore, it is only because man believes himself to be free, not because he is free, that he experiences guild. Guild is also something you can unlearn, and it also depends on where you live, in what kind of culture, we don’t even know how old this feeling is. Nobody is responsible for his actions, nobody for his nature, to judge is identical with being unjust. This also applies when an individual judges himself. The theory is as clear as sunlight, and yet everyone prefers to go back into the shadow and the untruth, for fear of the consequences.

The history of the impression we use to judge someone’s responsibility for their actions has the following stages. First you have good and bad actions that are judged by the results, soon these results are forgotten, and the actions are now just good or bad. Then the goodness or badness is implanted in the motive, and the action in itself is looked upon as morally ambiguous. Than we goes further by designating good or bad to a whole person instead of their actions. To evaluate, man is made responsible for his effects (the results), then for his actions, then for his motives, and finally for his nature. But finally, man discovers that our nature is determined by his place in time and space and that there is no free will. Schopenhauer does not agree with this and points out that some actions give you guild and therefore require the need for you to be responsible, if you were not responsible you could not have felt guild. But man himself, because of his determinism, is precisely the being that he is—which Schopenhauer denies. Because we can feel guild Schopenhauer thinks he can prove our liberty not with regard to what we do, but with regard to our nature, we have the freedom to be this or that way, but we cannot act this or that way. Out of the sphere of freedom and responsibility, comes the sphere of strict causality, necessity, and irresponsibility. The feeling of guild comes apparently from causality, but in reality, it comes from our freedom which is the action of a free will, the fundamental cause of the existence of an individual, his will is there before his existence. Here the twisted reasoning is followed, that the fact that there is guilt inferred the justification, the rational acceptability comes from this, this is how Schopenhauer arrives at his fantastic sequence of the so-called intelligible freedom. But the guild after the deed is not necessarily reasonable, it is most certainly not, because it is based on the wrong presumption that the feeling of guild is not a necessary result. Therefore, it is only because man believes himself to be free, not because he is free, that he experiences guild. Guild is also something you can unlearn, and it also depends on where you live, in what kind of culture, we don’t even know how old this feeling is. Nobody is responsible for his actions, nobody for his nature, to judge is identical with being unjust. This also applies when an individual judges himself. The theory is as clear as sunlight, and yet everyone prefers to go back into the shadow and the untruth, for fear of the consequences.

We will never know if psychological observations are good or bad for society, but science needs it. Science however, is not interested in final aims, just like nature. But like a good copier of nature, science will also come up with useful ideas that benefit mankind, it does this also without intention. But whoever feels too chilled by the breath of such a reflection has perhaps too little fire in himself. But look around and you see them, people that are made of fire and who are not afraid of these ideas. Additionally, like serious people need some joy and enthusiastic people need something heavy to aide their health, should not we, intellectuals, who grow more inflamed, not be cooled down as to maintain a certain harmlessness and maybe be useful in this age as a mirror for self-reflection?

We will never know if psychological observations are good or bad for society, but science needs it. Science however, is not interested in final aims, just like nature. But like a good copier of nature, science will also come up with useful ideas that benefit mankind, it does this also without intention. But whoever feels too chilled by the breath of such a reflection has perhaps too little fire in himself. But look around and you see them, people that are made of fire and who are not afraid of these ideas. Additionally, like serious people need some joy and enthusiastic people need something heavy to aide their health, should not we, intellectuals, who grow more inflamed, not be cooled down as to maintain a certain harmlessness and maybe be useful in this age as a mirror for self-reflection?

Whatever you think of philosophy, the reanimation of moral observation is necessary. Important for this is the science that ask for the origins of moral sentiments and that solves complicated sociological problems, something the older philosophy did not do. The consequences can be seen in the wrong explanation of certain human actions and sensations by great philosophers. Like with the idea of unselfish actions and the false ethics that came from it, followed by a confused religion and a clouding of common sense. But superficial psychology seems to be the biggest enemy of progress and there is a lot of tedious work ahead. There is also a lot of bourgeoisie in popular psychology and serious researcher have to overcome that hurdle and make it a respectable science again, but results are already coming in from them. You can read it in the book: “On the Origin of Moral Sensations“ from Paul Ree.1 ” The moral man,” he says, ” is no nearer to the intelligible (metaphysical) world than is the physical man.” This idea, hardened by historical knowledge, may bringing down the ” metaphysical need ” of man, and if this good or bad for general wellbeing is hard to say, but it is important, and both fruitful and terrible like every two-face is looking in the world.

Whatever you think of philosophy, the reanimation of moral observation is necessary. Important for this is the science that ask for the origins of moral sentiments and that solves complicated sociological problems, something the older philosophy did not do. The consequences can be seen in the wrong explanation of certain human actions and sensations by great philosophers. Like with the idea of unselfish actions and the false ethics that came from it, followed by a confused religion and a clouding of common sense. But superficial psychology seems to be the biggest enemy of progress and there is a lot of tedious work ahead. There is also a lot of bourgeoisie in popular psychology and serious researcher have to overcome that hurdle and make it a respectable science again, but results are already coming in from them. You can read it in the book: “On the Origin of Moral Sensations“ from Paul Ree.1 ” The moral man,” he says, ” is no nearer to the intelligible (metaphysical) world than is the physical man.” This idea, hardened by historical knowledge, may bringing down the ” metaphysical need ” of man, and if this good or bad for general wellbeing is hard to say, but it is important, and both fruitful and terrible like every two-face is looking in the world.

Is there a downside to psychological observations? Are we aware of the downside so we can divert future intellectuals away from it? It is better for the general well being to believe in the goodness of men and have shame for the nakedness of the soul, these qualities are only useful when psychological sharp-sightedness is needed, this believe in the goodness of men might as well been for the best. When one imitates Plutarch’s1 heroes with enthusiasm and don’t want to see their motives you will benefit society with that, but not the truth, the psychological mistake and weakness when you do this is beneficial for humanity. Truth is better served with the words used by La Rochefoucauld in his forward to “Sentences et maximes morales.”3: “That which the world calls virtue is usually nothing, but a phantom formed by our passions to which we give an honest name so as to do what we wish with impunity.” He, and others like Paul Rée4 resemble good marksmen who again and again hit the bull’s-eye of human nature. What they do is amazing but the small minded people that are not driven by science but by love for mankind will condemn them.

Is there a downside to psychological observations? Are we aware of the downside so we can divert future intellectuals away from it? It is better for the general well being to believe in the goodness of men and have shame for the nakedness of the soul, these qualities are only useful when psychological sharp-sightedness is needed, this believe in the goodness of men might as well been for the best. When one imitates Plutarch’s1 heroes with enthusiasm and don’t want to see their motives you will benefit society with that, but not the truth, the psychological mistake and weakness when you do this is beneficial for humanity. Truth is better served with the words used by La Rochefoucauld in his forward to “Sentences et maximes morales.”3: “That which the world calls virtue is usually nothing, but a phantom formed by our passions to which we give an honest name so as to do what we wish with impunity.” He, and others like Paul Rée4 resemble good marksmen who again and again hit the bull’s-eye of human nature. What they do is amazing but the small minded people that are not driven by science but by love for mankind will condemn them.

Thinking about our human behavior can make life easier, if you do this it will make you more aware, even in difficult situations it will give you guidelines and make you feel better. This was once common knowledge but is now forgotten? It is clearly visible in Europe, not so much in literature and philosophical writings, because they are the works of exceptional individuals, but in the judgments on public events and personalities by the people, especially the lack of psychological analysis is noticeable in every rank of society where there is a lot of talk about men but not much about man. Why do we not talk or read more about this rich and harmless subject? Almost no one reads La Rochefoucault or similar books with maxims1, and even rarer are the ones that not blame these writers. But even these exceptional people that read it have a hard time finding all the pleasure in these maxims because they have never tried to make them themselves. Without this path of studying and polishing it will look easier than it is, and he will find therefore les pleasure in reading these maxims. So, they look like people who praise because they cannot love, and are very ready to admire, but still more ready to run away.

Thinking about our human behavior can make life easier, if you do this it will make you more aware, even in difficult situations it will give you guidelines and make you feel better. This was once common knowledge but is now forgotten? It is clearly visible in Europe, not so much in literature and philosophical writings, because they are the works of exceptional individuals, but in the judgments on public events and personalities by the people, especially the lack of psychological analysis is noticeable in every rank of society where there is a lot of talk about men but not much about man. Why do we not talk or read more about this rich and harmless subject? Almost no one reads La Rochefoucault or similar books with maxims1, and even rarer are the ones that not blame these writers. But even these exceptional people that read it have a hard time finding all the pleasure in these maxims because they have never tried to make them themselves. Without this path of studying and polishing it will look easier than it is, and he will find therefore les pleasure in reading these maxims. So, they look like people who praise because they cannot love, and are very ready to admire, but still more ready to run away.

Is our philosophy now a tragedy? is truth hostile to life and improvement? Can we live in a lie, or is death better? Because, there is no “must do”, our way of seeing the world has destroyed morality. Our knowledge only excepts pleasure and pain, benefit, and injury as grounds for action, but how do they work with the truth? Our preferences or dislikes make wrong assessments and determine with it our pleasure and pain. Human life is one big lie, and no one can escape this without cursing his past and finding his present motives, like honor, worthless and the ideals that drive him seem ridiculous. Is there only despair left with a philosophy of destruction? I think this is determined by the temperament of man. I can imagine a life that is less affected by emotions and it would slowly lose it’s bad habits through the influence of knowledge. Finally, you could live amongst men and on selves without praise, reproach, or agitation, feasting one’s eyes, as if it were a play, upon much of which one was formerly afraid. No more emphasis and attention on the thought that one is nature or more than nature. You need a more positive stance in life and not the qualities of old dogs and people chained for too long. You need people that live for knowledge and can live with less and ignore common values and practices. This person like to share this pleasure and lifestyle, it’s probably the only thing he can share to his detriment. But if more is asked of him he will point to his brother, the free man of action, with a slight scorn because his freedom is a particular one.

Is our philosophy now a tragedy? is truth hostile to life and improvement? Can we live in a lie, or is death better? Because, there is no “must do”, our way of seeing the world has destroyed morality. Our knowledge only excepts pleasure and pain, benefit, and injury as grounds for action, but how do they work with the truth? Our preferences or dislikes make wrong assessments and determine with it our pleasure and pain. Human life is one big lie, and no one can escape this without cursing his past and finding his present motives, like honor, worthless and the ideals that drive him seem ridiculous. Is there only despair left with a philosophy of destruction? I think this is determined by the temperament of man. I can imagine a life that is less affected by emotions and it would slowly lose it’s bad habits through the influence of knowledge. Finally, you could live amongst men and on selves without praise, reproach, or agitation, feasting one’s eyes, as if it were a play, upon much of which one was formerly afraid. No more emphasis and attention on the thought that one is nature or more than nature. You need a more positive stance in life and not the qualities of old dogs and people chained for too long. You need people that live for knowledge and can live with less and ignore common values and practices. This person like to share this pleasure and lifestyle, it’s probably the only thing he can share to his detriment. But if more is asked of him he will point to his brother, the free man of action, with a slight scorn because his freedom is a particular one.

Every belief in the value and worthiness of life is based on impure thinking. It is only possible because of a lack of compassion for mankind. The few that think further only do this in a limited way. If you, for example, only look at the gifted people, and see them as the purpose of life and rejoice their activities, then you might believe in the value of life, but you have to ignore the rest and thus think impure. The same goes for when you only look at one human trade, the les egoistical, and forget about the rest. But either way you are an exception if you think like that. But most people don’t complain about life and value it as it is, they only look at themselves and don’t look beyond themselves like the beforementioned exceptions. The lack of imagination and compassion shields him for the fate of others. The person with compassion will, then again, have a low value of life, and if he could understand it all he would curse life, because it has no goal. He who sees this will not find comfort in life, even in his own. But feeling lost as humanity and as an individual like a blossom in nature is greater than all other feelings, but who can handle that? Probably the poet, they know how to console themselves.

Every belief in the value and worthiness of life is based on impure thinking. It is only possible because of a lack of compassion for mankind. The few that think further only do this in a limited way. If you, for example, only look at the gifted people, and see them as the purpose of life and rejoice their activities, then you might believe in the value of life, but you have to ignore the rest and thus think impure. The same goes for when you only look at one human trade, the les egoistical, and forget about the rest. But either way you are an exception if you think like that. But most people don’t complain about life and value it as it is, they only look at themselves and don’t look beyond themselves like the beforementioned exceptions. The lack of imagination and compassion shields him for the fate of others. The person with compassion will, then again, have a low value of life, and if he could understand it all he would curse life, because it has no goal. He who sees this will not find comfort in life, even in his own. But feeling lost as humanity and as an individual like a blossom in nature is greater than all other feelings, but who can handle that? Probably the poet, they know how to console themselves.

Our judgements concerning life are illogical and therefore unjust. The first reason for this is the partial availability of the material we work with, and then how we make conclusions out of it, and finally, the fact that every separate piece of the material is unavoidably the result of impure knowledge. If we know someone for a long time we still have not enough information to give a final evaluation, every evaluation is premature and should be. We are the one that measures, and we are ever changing. Our mood swings prevent us from making a stable platform from where we can measure the other Maybe the conclusion is that we should not judge at all. If we could just live without guesses, and favorites because they depend on your flawed evaluation. A drive towards or away from something without a need or avoidance, or an evaluation of the worth of the goal doesn’t exist. We know that we are unjust and illogical, and it is a disharmony of existence.

Our judgements concerning life are illogical and therefore unjust. The first reason for this is the partial availability of the material we work with, and then how we make conclusions out of it, and finally, the fact that every separate piece of the material is unavoidably the result of impure knowledge. If we know someone for a long time we still have not enough information to give a final evaluation, every evaluation is premature and should be. We are the one that measures, and we are ever changing. Our mood swings prevent us from making a stable platform from where we can measure the other Maybe the conclusion is that we should not judge at all. If we could just live without guesses, and favorites because they depend on your flawed evaluation. A drive towards or away from something without a need or avoidance, or an evaluation of the worth of the goal doesn’t exist. We know that we are unjust and illogical, and it is a disharmony of existence.