I think, therefore I am is what Descartes famously said. He seems to clarify later that the thinking is undeniable, but that little can yet be concluded about the nature of the thinker. A critique that you can make, and is made, is the “I” in this phrase. How could Descartes concluded thet the “I” he identifies with is the thing that does the thinking?

It is hard to ignore the feeling that there is something in us that does the thinking and that we call I. The reason is that I feel like I think about it. But the I that thinks is also the I that makes bodily sounds, and how much do you control those?

In light of this, “I” seems more like a linguistic tool we use to communicate with others and with ourselves. Our bodies breathe and digest without our intervention, yet we still say that we breathe and digest, just as we say “I think this or that,” even though our control over thinking may not be very different.

But man’s craving for grandiosity is now suffering the third and most bitter blow from present-day psychological research which is endeavouring to prove to the “ ego ” of each one of us that he is not even master in his own house, but that he must remain content with the veriest scraps of information about what is going on unconsciously in his own mind.

Freud, Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, Part III, Lecture XVIII (https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.278046/page/241/mode/2up)

As far as the superstitions of the logicians are concerned: I will not stop emphasizing a tiny little fact that these superstitious men are loath to admit: that a thought comes when “it” wants, and not when “I” want. It is, therefore, a falsification of the facts to say that the subject “I” is the condition of the predicate “think.” It thinks: but to say the “it” is just that famous old “I” – well that is just an assumption or opinion, to put it mildly, and by no means an “immediate certainty.” In fact, there

is already too much packed into the “it thinks”: even the “it” contains an interpretation of the process, and does not belong to the process itself. People are following grammatical habits here in drawing conclusions, reasoning that “thinking is an activity, behind every activity something is active, therefore –.” Following the same basic scheme, the older atomism looked behind every “force” that produces effects for that little lump of matter in which the force resides, and out of which the effects are produced, which is to say: the atom. More rigorous minds finally learned how to make do without that bit of “residual earth,” and perhaps one day even logicians will get used to making do without this little “it” (into which the honest old I has disappeared).

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyong Good and Evil, On the prejudices of philosophers, §17

The next quote is from Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein is known for his philosophy of language and for the ways in which language influences our lives. In this passage, he argues that when we talk about pain, the way we talk about it pushes us to believe that pain must be something we can locate inside ourselves. According to Wittgenstein, this belief is not demanded by our experience of pain itself, but by the grammar of the language we use to describe it.

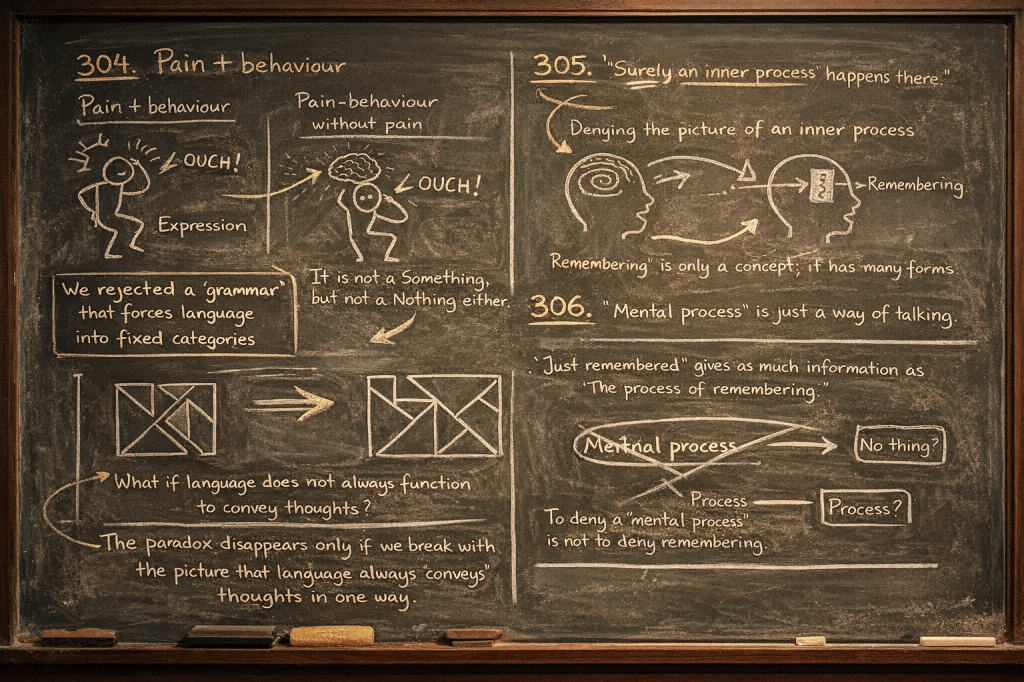

304.“But you will surely admit that there is a difference between pain-behaviour with pain and pain-behaviour without pain. Admit it? What difference could be greater! — And yet you keep arriving at the conclusion that the sensation is a Nothing. — Not at all. It is not a Something, but not a Nothing either! The conclusion was only that a Nothing would serve just as well as a Something about which nothing can be said. We merely rejected the grammar that tries to force itself on us here.

The paradox disappears only when we radically break with the idea that language always functions in one way, always serves the same purpose: to convey thoughts — whether those thoughts concern houses, pain, good and evil, or whatever else.”

305.“But you surely cannot deny that, for example, in remembering an inner process takes place. — Why then does it seem as if we wanted to deny something? When one says ‘Surely an inner process takes place there’ — one wants to go on: ‘You can see that. And it is this inner process that you mean by the concept of “remembering.”’ The impression that we want to deny something arises from the fact that we turn against the picture of an ‘inner process.’ What we deny is that this picture gives us a correct idea of the use of the word ‘remembering.’ On the contrary, we say that this picture, with all its ramifications, prevents us from seeing the use of the word as it is.”

306.“Why then should I deny that there is a mental process? Only because ‘There has taken place in me the mental process of remembering’ means nothing other than: ‘I have just remembered …’. To deny the mental process would mean to deny remembering; to deny that someone remembers something.”

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Filosofische onderzoekingen, §§304–306. (translated from Dutch to English by me)