The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, 1995

ABSTRACTION. A putative psychological process for the acquisition of a concept x either by attending to the features common to all and only xs* or by disregarding just the spatiotemporal locations of xs. The existence of abstraction is endorsed by Locke in the Essay Concerning Human Understanding (esp. II. xi. 9 and 10 and III. iii. 6 ff.) but rejected by Berkeley in The Principles of Human Knowledge (esp. paras. 6 ff. and paras. 98, 119, and 125). For Locke the capacity to abstract distinguishes human beings from animals. It enables them to think in abstract ideas and hence use language. Berkeley argues that the concept of an abstract *idea is incoherent because it entails both the inclusion and the exclusion of one and the same property. This in turn is because any such putative idea would have to be general enough to subsume all xs yet precise enough to subsume only xs. For example, the abstract idea of triangle ‘is neither oblique nor rectangular, equilateral norscalenon, but all and none of these at once’ (The Principles of Human Knowledge, Introduction, para. 13).

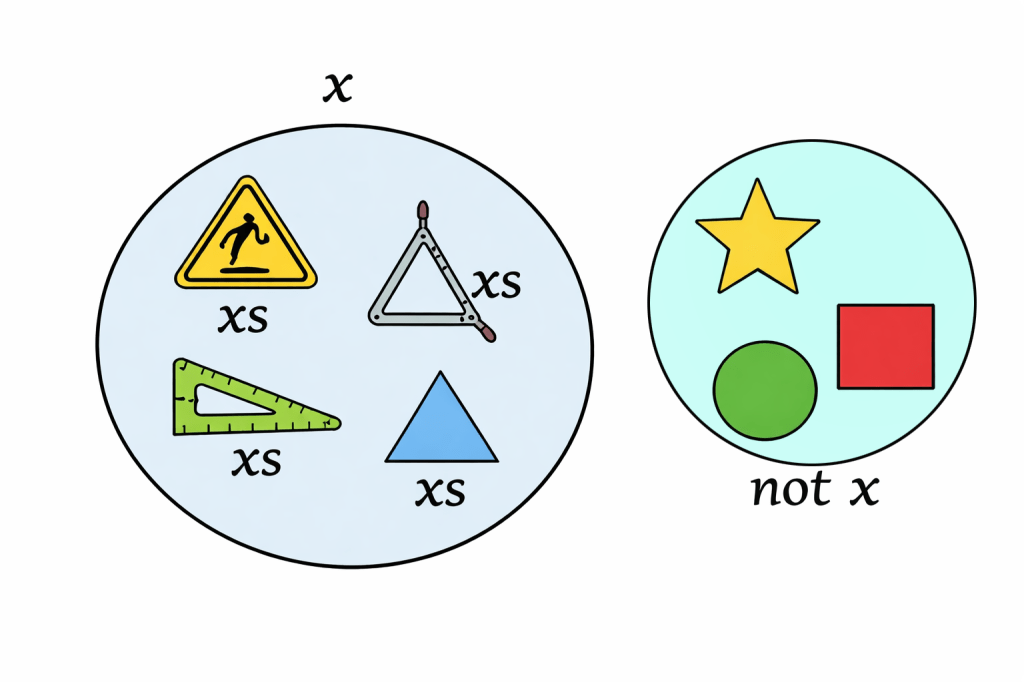

* x stands for a general category, and xs means the individual things that belong to that category.

Example:

If x = triangle, then xs are all the particular triangles (this drawn triangle, that road sign, any triangle at all).

When philosophers say “all and only xs,” they mean everything that is a triangle, and nothing that is not a triangle. The notation is just a way of talking about a category and the things that fall under it.

AI

Abstraction is the mental or conceptual process of isolating certain features of things while ignoring others, in order to form general ideas or concepts. When you abstract, you move away from particular, concrete instances and focus on what they have in common. For example, from many individual trees you abstract the concept tree; from different acts of exchange you abstract money or value. In philosophy, abstraction explains how we form general concepts, mathematical objects, and properties. It is often contrasted with concretion: abstraction removes detail, context, and individuality. Different traditions treat abstraction differently.

– Aristotle: abstraction is grounded in experience; universals are derived from particulars.

– Plato: abstraction points toward independently existing forms.

– Modern empiricism: abstraction is a cognitive operation performed by the mind.

Wikipedia

Abstraction is the process of generalizing rules and concepts from specific examples, literal (real or concrete) signifiers, first principles, or other methods. The result of the process, an abstraction, is a concept that acts as a common noun for all subordinate concepts and connects any related concepts as a group, field, or category.[1]

Abstractions and levels of abstraction play an important role in the theory of general semantics originated by Alfred Korzybski. Anatol Rapoport wrote “Abstracting is a mechanism by which an infinite variety of experiences can be mapped on short noises (words).” An abstraction can be constructed by filtering the information content of a concept or an observable phenomenon, selecting only those aspects that are relevant for a particular purpose. For example, abstracting a leather soccer ball to the more general idea of a ball selects only the information on general ball attributes and behavior, excluding but not eliminating the other phenomenal and cognitive characteristics of that particular ball. In a type–token distinction, a type (e.g., a ‘ball’) is more abstract than its tokens (e.g., ‘that leather soccer ball’).

Origins

Main article: Behavioral modernity

Thinking in abstractions is considered by anthropologists, archaeologists, and sociologists to be one of the key traits in modern human behaviour, believed[3] to have developed between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago. Its development is likely to have been closely connected with the development of human language, which (whether spoken or written) appears to both involve and facilitate abstract thinking. Max Müller suggests an interrelationship between metaphor and abstraction in the development of thought and language.

History

Abstraction involves induction of ideas or the synthesis of particular facts into one general theory about something. Its opposite, specification, is the analysis or breaking-down of a general idea or abstraction into concrete facts. Abstraction can be illustrated by Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum (1620), a book of modern scientific philosophy written in the late Jacobean era of England to encourage modern thinkers to collect specific facts before making any generalizations.

Bacon used and promoted induction as an abstraction tool; his induction complemented but was distinct from the ancient deductive-thinking approach that had dominated the Western intellectual world since the times of Greek philosophers like Thales, Anaximander, and Aristotle. Thales (c. 624–546 BCE) believed that everything in the universe comes from one main substance, water. He deduced or specified from a general idea, “everything is water,” to the specific forms of water such as ice, snow, fog, and rivers.

Early-modern scientists used the approach of abstraction (going from particular facts collected into one general idea). Newton (1642–1727) derived the motion of the planets from Copernicus’ (1473–1543) simplification, that the Sun is the center of the Solar System; Kepler (1571–1630) compressed thousands of measurements into one expression to finally conclude that Mars moves in an elliptical orbit about the Sun; Galileo (1564–1642) compressed the results of one hundred specific experiments into the law of falling bodies.

Read the rest here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abstraction